#131 Honoring our Legacy

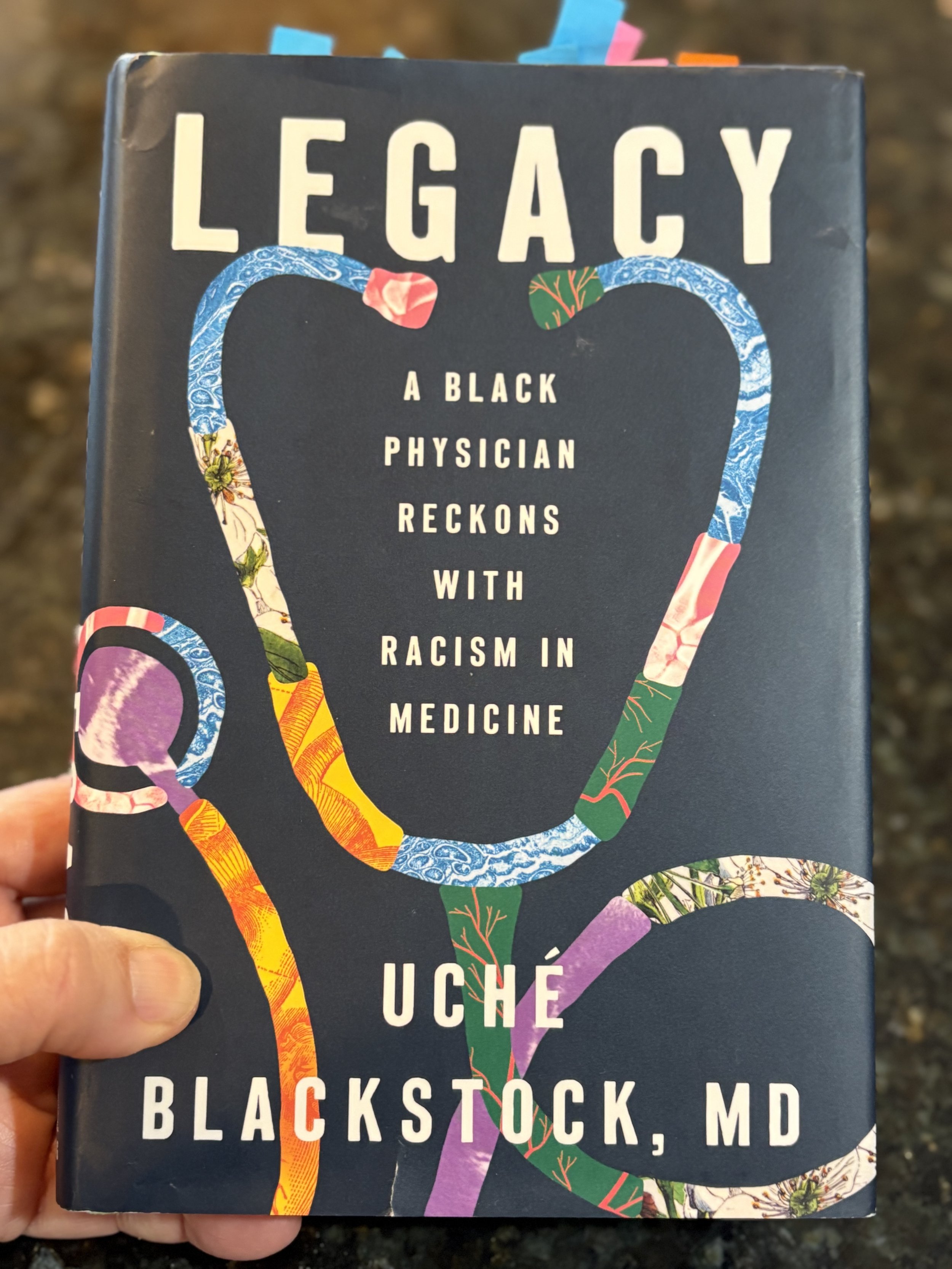

Uché Blackstock’s memoir calls us to reckon with racism in medicine

photo by Joan Naidorf

This review was first published in The DO Magazine.

As we celebrate Black History Month this February, we wanted to focus on stories of Black physicians and their thoughts about the state of health care and the disparities experienced in minority communities. Uché Blackstock, MD, really delivers in her bestselling book, “Legacy: A Black Physician Reckons with Racism in Medicine.” Published by Viking Press, this book is primarily a family and personal memoir. Dr. Blackstock tells how she became a Harvard-educated emergency medicine (EM) physician, embarking on an academic career while trying to help diversify the student body and residency training programs of a major university medical center.

The author includes the story of her mother, Dale Gloria Blackstock, MD, the child of a poor immigrant family in Brooklyn who, despite lack of mentorship, attended Harvard Medical School. Dr. Dale Gloria Blackstock returned to her Brooklyn Crown Heights neighborhood to work as an internist at Kings County Hospital Center, serving her neighbors and community members.

The author’s mother worked through infertility issues to give birth to twin girls, Uché and Oni. Their parents set an impeccable example of dedication to education, advancement and serving their community. Both girls would follow the path their mother set to attend Harvard as undergraduates and Harvard Medical School.

First-hand experiences

The chapters recounting the tragic loss of Dr. Dale Gloria Blackstock to leukemia while in her 40s demonstrate the heartbreaking realities of delayed diagnosis and poorer outcomes for Black cancer patients. Her daughters soldiered through their grief and became distinguished physicians. Both developed a strong interest in public health and how minority populations were being undertreated or ignored in the medical system.

Beyond the experiences of the author and her family, “Legacy” reviews aspects of racism in our society and how these impact the availability of healthy food, clean water, primary care and acute care in Black communities. Despite advances in technology and innovation in recent decades, the author points out that “health outcomes have gotten worse, not better, for Black Americans.” (p. 6)

The statistics regarding the health of Black Americans are startling. Dr. Blackstock writes,

“Today we are in the midst of an undeniable maternal mortality crisis in the United States, largely driven by the deaths of Black birthing people, who are three to four times more likely to die than their white peers … Black men have the shortest life expectancy of any major demographic group. Black babies have the highest infant mortality rate.” (p. 6)

The author addresses the historical context and system-wide inequities at the root of health care inequality and poor outcomes. As a medical student, Dr. Blackstock received the education we now know is so rooted in debunked beliefs.

Dr. Blackstock shares,

“Throughout my medical education, differences between Black and white patients were passed off as information, as data, as the objective truth. No one made the point that using race as an aid in diagnosis might lead to bias and stereotyping, which in turn could lead to misdiagnosis, thereby harming Black patients. Or perhaps more important, no one stated that race is, after all, a social construct invented during colonial times with no basis in science or genetic fact in the first place … I duly absorbed the message that people of different racial backgrounds have different criteria for what are considered normal laboratory values and that the reason for this was likely biological. The message was clear. We, Black people, had impaired functioning because of our race. Whereas the more accurate statement would be that oftentimes the impaired functioning was because of racism.” (p. 80)

The struggles that Black and other minority group patients face in the American medical system is illustrated by the author’s own experience as a patient. She shares the troubling account of her own delayed appendicitis diagnosis while attending Harvard Medical School. The episode demonstrates both the minimizing of her symptoms and the misdiagnosis that frequently affects people of color and women.

The challenge of creating systemic change

When Dr. Blackstock took a position in the emergency medicine department of New York University, she got an insider’s look into the racism and sexism of academia as well. When she found herself stretched too thin while she was starting an ultrasound training program, founding a fellowship and mentoring minority students, she was censured by administrators.

The author shares the frustrations of trying to make changes from within as a Black person. The challenges of speaking up while trying not to offend people and the limitations of her workplace became too great. She quit academia and moved to practice urgent care in her community and became a subject expert and consultant on racism in the medical system. She wrote articles, appeared on television and eventually testified before Congress on issues of racism in medical training and the inequities in the health care of Americans.

When it seems that she could not pack any more into her book, Dr. Blackstock chronicles her experiences of treating COVID-19 as a community urgent care physician in New York City during 2020. She addresses the mistrust of the Black community due to medicine’s historical mistreatment of and cruelty toward Black patients over the years. She connects this sad history to COVID-vaccine reluctance and inaccessibility in the early days of the vaccine rollout.

Even the standard technology being used to monitor oxygenation was exposed as inadequate for some Black patients. The relative insensitivity of pulse-oximetry on darkly pigmented skin made Black people seem healthier than they actually were. Black patients with dark pigmentation might not be offered the level of aggressive treatment that they are rightly due.

Dr. Blackstock became a television network medical contributor on the intersection of health care and racism, primarily the heavy toll that the pandemic took on the Black community in America. “If nothing else, unlike anything had in the past, the pandemic opened much of the public’s eye to systemic racism in health care,” she wrote. (p. 238)

The first step in the process of making change, Dr. Blackstock writes, is awareness of current inequities and faulty assumptions. I believe this is the step that many practicing physicians and administrative officers will find the hardest. All humans have adopted strong biases in the way they were raised and trained. Some injustices baked into the system are difficult to recognize because of our entrenched medical system and the longstanding traditions of how things have always been.

Inspiration in the pages

To finish, Dr. Blackstock has strong recommendations for people of all races, medical professionals, health care administrators and politicians on how the inequities and injustice in medical care can be addressed.

“The health care system needs to give practitioners of all backgrounds a framework for understanding what Black patients and communities have gone through in this country for centuries and what they are still enduring,” she said. (p. 7)

Dr. Blackstock delivers on an ambitious premise for a book of about 275 pages. Her personal and family memoir is inspiring. Many will find alarming the information she shares on the history of experimentation on enslaved people and the normalization of race-based testing. This is an important book that should be read by both physicians and members of the public. Medical school deans would be well-advised to choose it as a community read. It will educate and stimulate discussion that will hopefully lead to meaningful change.