#61 Don’t Attack the Messenger

My colleague and friend, Dr. Cleve Francis, sent a link to his recent Medscape article: No, You Can't See a Different Doctor (medscape.com). After a lengthy and distinguished career as a cardiologist in our community, Dr. Francis has taken on a role as Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisor at the large, local health system. He shared a blogpost with a larger national audience to highlight the issue of bigotry amongst some of our patients and the ways in which his health care system will deal with this behavior and set expectations for our patients.

Not surprisingly, his article brought a robust response of people who took issue with some of his views. There are many thoughtful and respectful comments made by readers. Then the comments take a turn for the worse: personal attacks, invalidation, and mischaracterization. Some of the responses seem directed at the title of the piece, which was undoubtedly written by the Medscape editors to get more clicks on the article. The words of Dr. Francis are more about establishing some accountability parameters for the behaviors of patients in healthcare settings with the purpose of protecting the rights of doctors, nurses, and other professionals from being insulted, harassed, or mistreated.

To encourage a diverse work force, we recruit people of all ethnic, racial, and gender backgrounds. If those people do not feel that their work is judged fairly or that they are safe both physically and emotionally, they will quit and go elsewhere. Do all of us need to handle occasional rejection and insults? Yes, we do. Can we do more to stand with all of our health care professionals to support them in a healing and nurturing environment? Yes, we can.

I read both of the linked documents and noted that there is no mention of denying patients emergency or urgent medical care. In the Mayo Clinic link, a thoughtful approach is presented that “allows us to address both microaggressions and egregious behavior in a manner that supports the rights and responsibilities of patients, staff, and the organization.” The pressure on hospital systems to support and retain well-trained nurses and physicians is strong. So many professionals are exiting from clinical medicine and leaving staff shortages.

Should a mature physician or nurse realize the bigoted and biased comments of some of our patients reflect on that patient’s own thoughts of fear and prejudice, not the skills of doctor or nurse offering the care. Yes, and as professionals grow in confidence and maturity, perhaps they can shrug off some bad behavior. But why not make set some standards of behavior that reflect civility and decency a part of the expectations made clear to a patient when that person enters the medical system. Dr. Francis references the Patient Code of Conduct adopted by the Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, more than 75 percent of the respondents to a survey of female family physicians in Ontario reported some sexual harassment by patients at some time during their careers. One can extrapolate that many of our female colleagues in the nursing profession have also been subjected to some form of unwanted touching, sexual advancements, comments, or insults. Most of us (I am an emergency physician) learn to grin and bear it in our roles as medical professionals.

To state that persons of color or women or some other historically marginalized group “shouldn’t feel that way” or “needs therapy” is at worst, a total invalidation of another person’s experience and at best, extremely insensitive. It may be difficult for some of us to see or understand the thoughts and feelings of people who don’t share the same gender, skin color, religious, or cultural backgrounds. That doesn’t mean those people are not experiencing discomfort or injustice. In our country, people get to think and feel the way they choose, whether we agree with them or not. I am speaking of our patients and our colleagues.

I believe that Dr. Francis is advocating a reasonable approach to discussing a rather sensitive topic. Even his referral to “zero tolerance” for discriminatory or biased behavior is not really accurate. Patients still get an opportunity to explain their requests or behaviors. The Mass General policy states, “If we believe you have violated the Code with unwelcome words or actions, you will be given the chance to explain your point of view. We will always carefully consider your response before we make any decisions about future care at Mass General Brigham.”

Most professionals would agree that if some patients may believe that a certain doctor or nurse treated them poorly or made an error on a previous encounter, it is probably better for both parties involved to have the patient be treated by another professional, if the circumstance allows. I vividly recall the time when a Muslim lady was bleeding out in the emergency department from some gynecologic problem. Her husband would not allow his wife to be treated by the male obstetrician - gynecologist who was on call and ready to take her to the operating room. The husband wanted to drive her to another hospital thirty minutes away. I pleaded with him not to try to find a lady OB-GYN who may or may not be on duty at that other hospital. He finally agreed to life-saving treatment by the physician on call.

Dr. Francis has served the community I live in as a cardiologist and philanthropist for forty-two years. His stature as a role model and mentor to his colleagues has been immeasurable. I cannot imagine how many young black doctors and nurses over the decades have looked at Dr. Francis when there were no other people of color in the room and thought: maybe I can do that too. To suggest, as one commentor did, that he is just some administrator telling other doctors how to practice is uninformed and incorrect.

Retelling the story of a racially insensitive remark was a tool for Dr. Francis to illustrate a point he was introducing about patient bias and how it made him feel as a much younger man. To minimize this interaction and suggest that perhaps it was not racially motivated or that he should just get some therapy to deal with prior trauma, is both gaslighting and dismissive. If your first response to this story is to suggest that the issue is not real or valid, your attitude might just be emblematic of the underlying problem.

I write and think a lot about the challenging interactions that physicians and healthcare professionals have with some of our patients. People who openly threaten, express bigotry, and insult us are most certainly the sort of “difficult” people I cover in my book, Changing How We Think About Difficult Patients. I discuss some of the errors in thinking on the part of both the patients and the healthcare professionals. Doctors and nurses tend to label people as difficult and that alone causes all sorts of suffering.

In his book, On Becoming a Healer, Dr. Saul Weiner talks a lot about “boundary clarity” in the minds of medical professionals. To paraphrase him, physicians must be able to distinguish between their own inner emotions and reactions to things such as a patient’s insults or request to see another person based on race or other bias. The doctor’s own emotions of anger or outrage may blind them to those patient behaviors that signify some sense of fear or stress. It would be ideal if young doctors and nurses could maintain boundary clarity when faced with some bad patient behavior, but that is a lot to ask of young and untested people.

Undoubtedly, Dr. Francis could tell of many incidents of racial prejudice both in and out of the hospital. In An Interview with Dr. Cleve Francis, he tells the story of an incident that occurred when he was a new attending. He was going into the physician entrance of this very suburban hospital, to enter the radiology department to review a chest X-ray on one of his first consults. He was dressed in casual attire. When the security guard lost sight of him, they called the local police force to look for a possible intruder. Dr. Francis had to introduce himself as the new cardiologist and he vowed to himself to always wear a coat and tie when he came to the hospital.

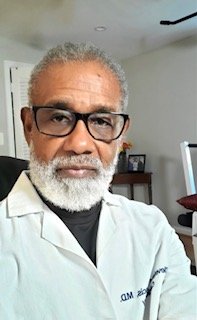

Dr. Cleve Francis Photo used with permission

Dr. Francis has developed thick skin over his 75 plus years. He can engage constructively on the merits, or not, of his work with the INOVA system as a Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Advisor. Readers are free to state their areas of disagreement in the Medscape comment section. Ad hominem arguments are not appropriate and quite undignified. To find solutions to any problem, we have to discuss the thoughts and opinions held on all sides of the issue. We need to find common ground and shared humanity in seeking answers to challenging questions.