#75 Messages from the Seder Table

Everything has a meaning, sometimes three.

Happy Passover! Every item on the seder table is placed there for some metaphorical or symbolic reason. After cooking and orchestrating another successful Passover Seder, I reflected on many of the items that I use at the table and what they mean to me. Most have multiple meanings that Jewish families mention and explain as part of the ceremonial retelling of the ancient exodus of our ancestors from enslavement in Egypt.

The Seder Table by Joan Naidorf

The most visible symbol of our ancestors’ experiences is the matzah, or unleavened bread. The legend goes that before our ancestors were rushing out of Egypt, they could not wait for their bread to rise and had to take the flat loaves with them into the desert. During the eight-day festival of Passover, some observant folks give up all bread and foods containing leavening agents. A passage in Deuteronomy calls the matzah the “bread of affliction.”

In 2014, I travelled with the Jacobi Medical Society of DC to visit Cuba and its dwindling but robust Jewish community. While in Havana, we visited the remaining Sephardic synagogue: Sinagogo Centro Hebreo Sefardi de Cuba. At that time, there was a very interesting exhibit in the lobby documenting the Jewish people of Cuba and the era of the Holocaust. Also in the foyer, some ladies were selling hand sewn challah covers for the Shabbat and holiday tables.

The traditional braided bread of the Sabbath, challah, and the matzoh of the seder table, are traditionally covered by a cloth. These have become highly decorative pieces of folk art that some families pass through the generations. The Cuban covers were quite simple, almost childish, in its roughly sewn white yarn border. The central tree sits atop the outline of the island of Cuba. They asked for 20 bucks and I was happy to help them out.

Our Cuban Matzoh cover phot by Joan Naidorf

The Jewish people of Cuba live a very egalitarian existence to all the other citizens of the communist state. (except some of those big shots, of course) They are all poor. Their bodega rations for rice and beans are quite meager. In a symbolic gesture of solidarity with my Cuban sisters, I started using this cloth from Cuba as the cover on our Seder table for our matzah the “Bread of Affliction.” I admire the way those Cuban ladies have held on to their traditions and their dignity despite their life of affliction.

A few years ago, I started using a particular silver Kiddish cup as our Cup of Elijah. Elijah’s cup is reserved for the prophet and at one point in the seder, the job of opening the front door is delegated to a child so that Elijah may enter if he happens to be in the neighborhood. From the New Union Haggadah,

“Legend has it that Elijah returns to earth from time to time to befriend the helpless… the Prophet Malachi promised that Elijah would come to turn the hearts of parents to children, and the hearts of children to parents, and to announce the coming of the Messiah when all mankind would celebrate freedom… Hence, he has a place in every Seder.” (p. 68)

At our house, this act means restraining Dolly the Poodle from taking off through the open door and running down our block in suburban Virginia.

I have chosen this small cup engraved with the name of my husband’s uncle: Sidney Naidorf. It was a gift given in 1963 from the B’nai Sholem Men’s Choir, which is engraved around the base. Sidney and his wife Leah Rose took over the family grocery store in St. Joseph, Missouri, and lived there for decades until they retired later in life to Sun City, AZ.

Sidney’s cup photo by Joan Naidorf

I met Sidney and Leah Rose a few times and heard the stories of their charm, generosity, and their love for dancing. We have an awesome picture of Sidney and his unit posing at the recently liberated (from Nazi German occupation) Arc de Triomphe in Paris from March 1, 1945. Sidney is one of those fellows in front kneeling down. Those young men knew that they had done something spectacular.

Photo from Paris, March 1, 1945 from Naidorf family collection

He and Leah Rose had no children. When they passed away, they divided their assets between their nieces and nephews with a share going to their synagogue, B’nai Sholem, back in St. Joe’s. To honor their memory, my husband and I used those funds to purchase pre-paid college tuition plans for our three children. Our kids made us look like geniuses when they all attended the excellent schools of our state university system.

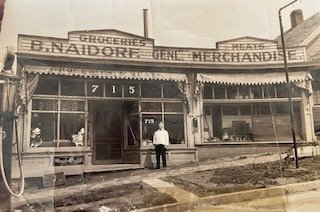

Who will remember Sidney and Leah Rose? We will. Every year when I take this cup out of our China cabinet and use it as our Cup for Elijah, I think about those two. I wonder if Sidney could really sing. Senator Jim Web wrote in his autobiography, Born Fighting, of Sidney’s smile and generosity to his family when Sidney extended credit and kindness to his financially strapped family during his childhood in St. Joseph. He was one of many small grocers in St. Joseph from an era that gave way to mega supermarkets run by huge corporations. Here is a photo of my husband’s grandfather, Benjamin, in front of his grocery store sometime in the early Twentieth Century.

The Naidorf Store in St. Joseph, MO, from family archive

The last symbolic table item I want to share are our napkin rings. My mother, Toby Sureck, loved to poke around antique stores and flea markets to pick up pretty little tchotchkes. One of the things that she collected were napkin rings. Napkin rings were invented in France in the 19th century and caught on in America amongst wealthy families. Families soon developed their own unique designs and personalized inscriptions for showing off their wealth and prestige to friends and guests. The most common rings were made from silver, but others were made with bone, wood, pearls, porcelain, glass, and other materials.

Napkin rings photo by Joan Naidorf

My mother collected the classic silver napkin rings, ceramic ones from China, and several other unique designs. Somehow that bag of rings landed in the sideboard of my dining room. One of the silver rings is inscribed with the name Beatty, the name of the street that I now live on. This feels like some sort of odd Karma to me. I cannot remember ever using the napkin rings during my childhood. My father would set up a large folding table into what used to be the entry room of our house which also served as the waiting room for his optometry practice. We hosted the Seder for the extended family that would frequently devolve into arguments amongst the grown-ups

Sometime after my mother passed away in 2010, I decided to start using the napkin rings on my Passover Seder table. As I polish them and admire each of the quirky designs, I think fondly of my mother and how she acquired them. I think she would be pleased that we are using them and her grandchildren keep coming home to our yearly family Seder. I love our table and all the messages it brings from the past. With the rebirth and liberation message of Passover, our future feels bright.